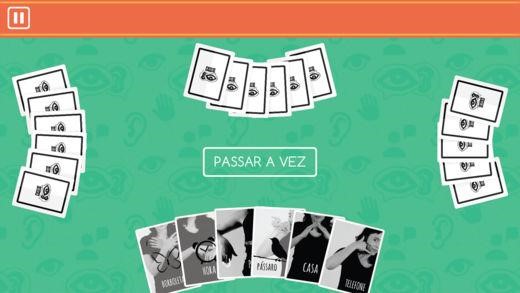

A gamer playing Librário, a video game developed to help people learn sign language. Image courtesy of Flávia Neves/Librário.

This article originally appeared on VICE Brazil."Educational challenges faced by deaf people in Brazil" was the essay prompt for 2017's ENEM, or National High School Exam: A non-mandatory, standardized Brazilian national exam that left many unprepared students surprised. The sheer volume of clueless responses—ranging from braille use and ramps, for instance—revealed the general public's ignorance regarding the hard of hearing community, and brought forth a discussion about social inclusion in different arenas. The video game industry is one of them.Vanderley Júnior is among the 9.7 million people with impaired hearing in Brazil, according to 2010 data from IBGE (the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics). Júnior was born in the capital city of Brasilia, works in finance, and is also known as Vaneov when he’s playing Dota 2 and League of Legends. Júnior, who lost his hearing when he was 11 months old after having meningitis, is 31 now and the founder of Deaf E-Sports League, which is the first league specifically created for the country's deaf population. On top of organizing tournaments and other events for the community, Júnior plays for Rabbits Deaf, a team which includes other deaf members.“I dream of being a professional player, entering a championship, and winning awards like all the other [non-deaf] people. I'm working [for] that dream to come true,” Júnior told Waypoint.In 2016, he decided to use his own investments to start a league for deaf gamers. The response from the community was enthusiastic and the competitions included participants from places beyond Brazil, such as Peru.

Júnior, who lost his hearing when he was 11 months old after having meningitis, is 31 now and the founder of Deaf E-Sports League, which is the first league specifically created for the country's deaf population. On top of organizing tournaments and other events for the community, Júnior plays for Rabbits Deaf, a team which includes other deaf members.“I dream of being a professional player, entering a championship, and winning awards like all the other [non-deaf] people. I'm working [for] that dream to come true,” Júnior told Waypoint.In 2016, he decided to use his own investments to start a league for deaf gamers. The response from the community was enthusiastic and the competitions included participants from places beyond Brazil, such as Peru. The idea to create the league came from the frequent issues Júnior had experienced when trying to communicate with non-deaf gamers. “A deaf player needs to type out the words and play at the same time, which is pretty complicated,” he said, adding that he felt naturally disadvantaged. “All the games need improvement. Specifically, [they need] to include sign language and video calling for deaf players.”At present, Brazil's video game industry doesn't have many initiatives that seek to create content for or about the deaf community. Aiming to change the way most games and players approach sign language, the developer Flávia Neves created Librário, a program that uses a card game to teach sign language.Neves, who’s pursuing a Master's degree in design at the State University of Minas Gerais, started the project to promote and teach sign language to people with varying degrees of hearing loss as well as those with perfect hearing. “Everybody knows or can identify playing cards, which is why we combined that visual kind of communication—using drawings and photos—with sign language,” she explained. “People can learn while they play.”

The idea to create the league came from the frequent issues Júnior had experienced when trying to communicate with non-deaf gamers. “A deaf player needs to type out the words and play at the same time, which is pretty complicated,” he said, adding that he felt naturally disadvantaged. “All the games need improvement. Specifically, [they need] to include sign language and video calling for deaf players.”At present, Brazil's video game industry doesn't have many initiatives that seek to create content for or about the deaf community. Aiming to change the way most games and players approach sign language, the developer Flávia Neves created Librário, a program that uses a card game to teach sign language.Neves, who’s pursuing a Master's degree in design at the State University of Minas Gerais, started the project to promote and teach sign language to people with varying degrees of hearing loss as well as those with perfect hearing. “Everybody knows or can identify playing cards, which is why we combined that visual kind of communication—using drawings and photos—with sign language,” she explained. “People can learn while they play.” The project has been backed by professors and scholarship holders—including Neves—and assisted by volunteers in the area. Librário was a hit in the public schools where the game was tested, getting both students and teachers interested in learning. The video game also won a national award, the Tecnologia Social da Fundação do Banco do Brasil, in 2015, and scored a sponsorship for the launch of its mobile version, available for iOS and Android users.Despite the success of the project, Neves highlights that developing a game for deaf people is challenging for many reasons: Dedication to research is required, and a crew of available interpreters (which isn’t always easy to find) is also needed, in addition to all of the essential expenses required for the development of any video game.“The first challenge is learning the language. We need to connect with the deaf users and with the sign language interpreters to choose the best signs for each word. The biggest difficulty we have with this project now is financial sustainability,” Neves said.The developer plans to move forward with Librário and update the game to include other themes related to sign language to improve the learning process for deaf and non-deaf players alike. “There’s a contemporary tendency to humanize technologies, spread empathy, and expand our abilities to understand other people’s hardships. It’s beyond necessary to develop games and tools of support to include every public segment.”

The project has been backed by professors and scholarship holders—including Neves—and assisted by volunteers in the area. Librário was a hit in the public schools where the game was tested, getting both students and teachers interested in learning. The video game also won a national award, the Tecnologia Social da Fundação do Banco do Brasil, in 2015, and scored a sponsorship for the launch of its mobile version, available for iOS and Android users.Despite the success of the project, Neves highlights that developing a game for deaf people is challenging for many reasons: Dedication to research is required, and a crew of available interpreters (which isn’t always easy to find) is also needed, in addition to all of the essential expenses required for the development of any video game.“The first challenge is learning the language. We need to connect with the deaf users and with the sign language interpreters to choose the best signs for each word. The biggest difficulty we have with this project now is financial sustainability,” Neves said.The developer plans to move forward with Librário and update the game to include other themes related to sign language to improve the learning process for deaf and non-deaf players alike. “There’s a contemporary tendency to humanize technologies, spread empathy, and expand our abilities to understand other people’s hardships. It’s beyond necessary to develop games and tools of support to include every public segment.”

Advertisement

Advertisement